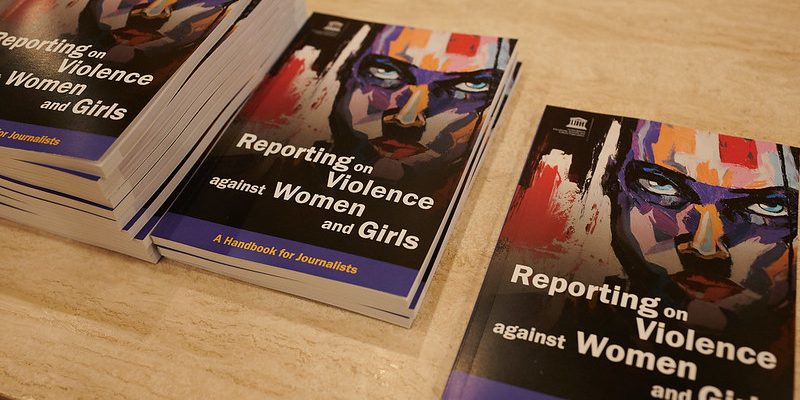

![]() The UNESCO launched a handbook for journalists on reporting violence against women and girls to help radio, television, press and social media professionals determine which channels of investigation and information is relevant and ethical when reporting on gender violence. This guide includes examples of good practices and tips on how to frame the topic, how to conduct an interview, how to avoid sensationalism, the terminology to use, etc.

The UNESCO launched a handbook for journalists on reporting violence against women and girls to help radio, television, press and social media professionals determine which channels of investigation and information is relevant and ethical when reporting on gender violence. This guide includes examples of good practices and tips on how to frame the topic, how to conduct an interview, how to avoid sensationalism, the terminology to use, etc.

This manual has three main objectives: firstly, to provide the keys required to understand the various forms of violence against women, like genital mutilations, the so-called «honour» killings, intimate partner violence or murders. These forms of violence are described in 10 information sheets which propose definitions of the different terms, statistics and explanations. Secondly, the manual aims at triggering a permanent reflection on journalism and the best way to inform on violence against women: which words and which images should we use, how to interview a woman who has suffered violence… Lastly, it suggests a number of advice and examples of good practices drawn from experienced reporters and codes of conduct used by different media around the world.

What, in your opinion, is the main problem journalists face when reporting about gender violence?

The coverage of violence against women fluctuates between silence and sensationalism too often. Even if the situation has evolved since the launch of the #MeToo movement, in most societies a heavy silence still surrounds the issue. However, although many journalists do an excellent work, when the media tackle the subject, sensationalism and hype are persistent, as was recently the case with the coverage of the violence committed by Daesh against Yezidi women, for instance, or with the use of rape as a weapon of war in the Eastern region of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

What is the most common mistake?

One of the major mistakes consists in only speaking of the aggressor while ignoring the victim, or in using an inadequate vocabulary which trivializes the act. For instance one should not use the expression «a seduction attempt» when it is a blatant sexual aggression. Similarly, one should avoid the expression «she confesses/admits to having been raped» (which suggests that she would have some responsibility) and one should replace it by «she was raped» or «she declares/reports that she was raped». Avoid euphemisms such as «marital dispute», which minimise reality. Instead, use the term «homicide», or the expression «intimate partner violence», depending on the situation. The manual proposes a reflection on the vocabulary as well as numerous concrete examples.

What would be the main recommendation?

The first recommendation would be to bring these violences out of the shadow and remind everyone that these are not private intrafamily disputes nor isolated incidents. They are recurring and systemic acts which affect society as a whole and involve us all. They emanate from historically unequal relations of power between men and women, which have established relations of domination and discrimination, as it was already underlined in the 1993 UN Declaration on the elimination of violence against women. One should, therefore, draw the coverage of these violences out of the miscellaneous news or «news in brief» columns where they are too often confined and approach them as societal phenomenons which deserve to be reported on the frontpage or in prime time in order to highlight their structural character.

Fonte: European Federation of Journalists

![]() Una ‘guida pratica’ per i giornalisti impegnati a raccontare gli episodi di violenza contro le donne. È la nuova iniziativa dell’UNESCO che in un agile volume propone buone pratiche e consigli utili ai professionisti dei media che si occupano di violenza di genere. La guida include, fra l’altro, suggerimenti su come inquadrare l’argomento, come condurre un’intervista, come evitare il sensazionalismo, come scegliere le parole più adatte da usare. Autrice di ‘Reporting on violence against women’ (questo il titolo del volume) è Anne-Marie Impe, giornalista, scrittrice, attivista per i diritti umani, docente di giornalismo, che in circa 150 pagine riporta definizioni, riferimenti normativi e link a istituzioni internazionali, storie e contesti culturali.

Una ‘guida pratica’ per i giornalisti impegnati a raccontare gli episodi di violenza contro le donne. È la nuova iniziativa dell’UNESCO che in un agile volume propone buone pratiche e consigli utili ai professionisti dei media che si occupano di violenza di genere. La guida include, fra l’altro, suggerimenti su come inquadrare l’argomento, come condurre un’intervista, come evitare il sensazionalismo, come scegliere le parole più adatte da usare. Autrice di ‘Reporting on violence against women’ (questo il titolo del volume) è Anne-Marie Impe, giornalista, scrittrice, attivista per i diritti umani, docente di giornalismo, che in circa 150 pagine riporta definizioni, riferimenti normativi e link a istituzioni internazionali, storie e contesti culturali.

«Nell’epoca del cambiamento digitale, democratico, sociale e politico – si legge nella prefazione firmata da Saniye Gulser Corat, direttrice del Dipartimento per la parità di genere, e Moez Chakchouk, responsabile del settore Comunicazione e informazione dell’Unesco – la comunicazione è diventata un mezzo cruciale per trasmettere idee e iniziative rivoluzionarie, in grado di creare comunità più forti, meglio informate e più impegnate che mai. L’esigenza di giornalismo etico è diventata centrale in tutte le redazioni ed è la pietra angolare di un giornalismo al servizio dello sviluppo della società».